隐匿性乙型肝炎的临床意义

介绍

隐匿性乙型肝炎(OBI)患者来源不同、受累肝脏形式不同,是临床上一种重要而又错综复杂的疾病。前者取决于患者在OBI诊断时的病史。一般来说,患者可分为三大类:第一类,患者有明确的急性乙型肝炎病毒(HBV)感染史;第二类,已知患者慢性乙型肝炎(CHB)感染(乙型肝炎表面抗原(HBsAg)持续阳性>6个月),并已进入感染的最后阶段,即HBsAg丧失(HBsAg血清清除率);第三类,患者既往无HBV感染史,且是首次就诊。在这三类可能的患者群体中,它们在OBI患者群体中的比例尚不清楚,因为没有大型流行病学研究解决这方面的问题。然而,预计第二组,即HBsAg血清清除的CHB感染者可能是OBI患者中比例最大的组,特别是在CHB高流行地区。有学者认为乙型肝炎病毒HBsAg基因突变患者也可归为OBI,原因是随着基因突变,它可能会改变乙肝表面抗原决定簇,从而逃避商业化乙肝表面抗原试剂的检测[1-3]。然而,多数研究表明,在大多数隐匿性乙肝患者中,不存在相应的HBV逃逸突变[4-6]。

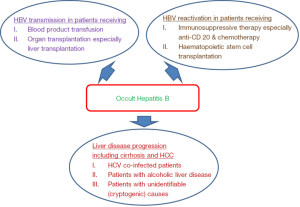

关于OBI的临床意义,它将在几个重要的临床领域发挥作用(图1)。首先,明确OBI受试者HBV感染的传播性是很重要的,这包括HBV通过OBI捐赠者的血液制品输注和器官移植进行传播;其次,我们还需要通过可测量参数去了解OBI对肝脏疾病的影响,如肝脏功能、肝脏组织学特征以及肝硬化、肝细胞癌等长期并发症;第三,了解OBI在其他慢性肝炎患者(如慢性丙肝感染和酒精性肝病)中的存在是否会对肝细胞癌的发展产生附加或协同的有害影响也很重要;最后,我们需要确定接受免疫抑制治疗的OBI患者HBV再次激活的风险。

病例分组

急性乙型肝炎感染患者

已经有充分的证据表明,乙型肝炎慢性化的机会取决于受试者首次感染乙型肝炎时的年龄。年龄小于1岁、1-5岁和5岁以上的患者,发生HBV慢性化的几率分别为90%、30%和2%[7]。因此,超过95%感染HBV的成年人不会导致HBV慢性化。大多数患者没有症状,他们在急性感染期间和缓解后产生抗HBS和抗HBC。那些有肝炎症状(如:不适、食欲不振、恶心和/或茶色尿)的患者可以提供更明确的急性HBV感染史。“急性”乙型肝炎的后果并不像以前认为的那么简单。1994年,Michalak和他的同事们证明了四名患者的血清和外周血单个核细胞(PBMC)中存在HBVDNA,这些患者在急性HBV感染发作后长达70个月才得以康复[8]。HBV在自限性急性乙型肝炎患者中的持续存在也被后续的研究证实[9,10]。虽然有证据表明急性HBV感染后病毒持续存在,但研究一致表明发生的肝脏坏死性炎症通常是轻微的[11,12]。动物实验也提供了有力的证据,在动物实验中,从急性肝炎中康复的土拨鼠有持续低水平的病毒复制,并伴有轻微的肝脏炎症[13]。此外,所有受试者的肝脏生化指标均正常。

一般认为,在急性乙型肝炎患者中存在OBI本身是无害的,因为肝脏各项指标没有太大变化。这些OBI患者产生的更重要的问题可能是当这些OBI患者接受免疫抑制治疗时,HBV是否有机会传染给其他人,以及HBV是否再次激活,下文将对此进行讨论。

HBsAg清除的CHB患者

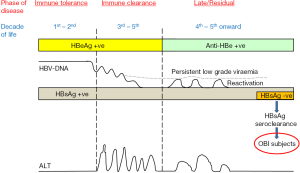

典型的CHB感染分为三个阶段,即免疫耐受期、免疫清除期和残留期(图2)。根据病毒复制状态、宿主的免疫应答以及在患者体内检测到的血清学结果,对这些阶段进行了明确的分类。HBsAg在前两期和残留期的大多数患者中均呈现持续阳性。然而,在年发病率0.1-0.8%[14]的部分残留期患者中有HBsAg清除现象发生。随着HBsAg血清清除时间的延长,血清中检测到HBVDNA的机会降低,HBsAg也变得无法检测[15]。根据Yuen等人的研究,HBsAg清除后1年、5-10年和超过10年的HBVDNA检出率分别为13%、6%和3.7%。然而,所有患者的肝脏中仍可检测到HBVDNA[15,16]。肝脏中检出的病毒其转录活性是很低的(HBV的核心、表面和X基因几乎不表达mRNA)[15,17],因此这些患者的肝脏组织学基本正常或接近正常[16,18]。根据在香港进行的一项研究表明,在29名接受肝脏活检的患者中,65%的患者没有发生坏死性炎症和纤维化,其余35%的患者的肝脏活检仅显示轻度坏死性炎症和/或纤维化[15]。在同一中心进行的另一项研究中,14例小于40岁且发生HBsAg血清清除的患者均未出现肝脏组织学纤维化[18]。关于HBsAg清除是否会发展为肝硬化和肝细胞癌,台湾的一项研究表明,如果患者没有原发性肝硬化或合并感染其他病毒性肝炎(如丙肝),其风险是较低的[19]。另一项台湾研究显示,HBsAg清除发生4年后,这些并发症的累积发生率为30%[20]。在香港的进一步研究表明,如果患者在HBsAg清除之前就已经有肝硬化,或者发生HBsAg清除患者的年龄超过50岁[15,18],则进展为肝细胞癌风险并不会降低。50岁以后和50岁之前HBsAg清除的患者相比,发生肝细胞癌的10年累计发生率分别为10%和0%(P=0.004)[15]。还应注意的是,在接受长期抗病毒治疗的患者中,约有10%的患者会发生HBsAg清除现象[21]。早期自发的HBsAg清除是否会产生良好临床预后,这种现象是否与药物诱导的HBsAg清除相关,还需要进一步研究。

既往无乙肝感染史的患者

OBI患者往往是通过献血中心用核酸检测(NAT)技术对血液制品进行筛查时被偶然发现的。因此,这些受试者通常没有个人乙肝病毒的感染史。他们可能是临床无症状的急性乙型肝炎患者或未知的慢性乙型肝炎且已发生HBsAg清除的患者。但是,他们可能也是主要的OBI患者但并没有传播HBsAg。

一项对40名OBI献血者的研究显示,抗HBc阳性39例(97.5%),抗HBs阳性36例(90%)[22]。无一例献血者抗-HBc和抗-HBs为阴性,这表示血清反应性呈现阴性的OBI是非常罕见的。此外,常见的表面抗原基因逃逸突变受试者无一例为阴性,如G145R,表明通过标准商业HBsAg检测逃逸的情况也不常见。这40名OBI受试者的肝脏生化指标均正常。中位坏死性炎症和纤维化评分分别为1和0,Ishak纤维化评分均小于2。30名OBI受试者(占比77%)、1名OBI受试者(占比3%)和5名OBI受试者(占比13%)分别检测了肝内HBV总DNA、cccDNA和基因组前RNA,结果肝内HBV总DNA中位数(0.22拷贝/细胞)较低。18名OBI受试者(占比45%)血清HBVDNA定量检测值>1.1IU/mL。

OBI的临床表现

乙肝病毒传播

乙型肝炎病毒传播的两种模式备受关注,分别是接受OBI捐献者血液制品的受者和接受器官移植,特别是OBI捐献者肝脏移植的受者。

含有HBVDNA的捐血血液制品具有潜在的感染能力,因此具有传染性。使用黑猩猩进行的动物研究表明,HBV最低50%的感染剂量低至10拷贝HBVDNA[23]。根据一项使用嵌合小鼠(严重免疫缺陷)接种OBI供体血清的研究[24]显示,4只接种小鼠中有1只检测出外周血HBVDNA、肝内HBVDNA、共价闭环(ccc)DNA以及肝组织HBcAg染色阳性。

因为一些众所周知的原因,记录OBI受试者的HBV传播性的研究很难进行。大多数研究必须依赖回顾性数据收集和供体—受体追踪才能完成。此外,输血前受体的HBV血清学数据无从查据,这些信息对于建立供体和受体之间的系统发展关系是极其重要的。尽管存在这些困难,一些研究已经证明它们之间的感染风险实际上是相当低的(1-3%)[24-26]。根据以往的回顾性研究,抗HBs阳性的OBI受试者的血液成分是非传染性的[26]。根据日本调查人员进行的一项研究,在12例输血相关的乙型肝炎病例中,所有捐血者的抗-HBc和抗-HBs均呈阴性(推测属于急性HBV感染的窗口期)[27]。

有研究表明,OBI献血者的抗-HBc阳性血液产品能够导致受体急性HBV感染[28-30]。然而,根据一项系统关联性研究显示,95%的抗-HBc阳性OBI献血者的传染率仅为2.2%[24],而一般传染率大约为2.4-3.0%[14]。这说明乙肝病毒虽然可以通过OBI受试者的血液制品传播,但传染率很低。HBV传染的机会取决于几个明确的参数,其中包括献血者和受血者的抗-HBs状态(血液中抗-HBs的存在与传染风险显著降低相关)、受血者输注血液制品的类型和数量,以及受血者的免疫抑制状态[26,27,31]。此外,由于血液中的乙肝病毒不同时期可能处于低水平波动状态,或者供体处于HBVDNA不可检测的时期[32],这也会影响HBV传播的机会。

OBI供者传播HBV的另一个渠道是器官移植,特别是肝脏移植。已有研究表明,在接受抗-HBc阳性供者肝脏移植的患者中,乙肝病毒感染发生率为22-100%[33,34]。抗-HBs和抗-HBc阴性的免疫抑制受体接受OBI供体的器官移植,其感染HBV的风险最高。血清抗体阴性OBI(抗-HBc和抗-HBs均为阴性)如何传播HBV尚不清楚。在另一种情况下,OBI受者在肝移植后由于免疫抑制治疗造成的免疫抑制状态而可能再次激活HBV。HBV新发感染或HBV激活引起的HBV感染,它们的临床表现往往比本身HBsAg阳性且复发HBV的受体要轻[33]。

与肝脏移植不同的是,在肾脏、心脏和骨髓等其他器官移植中,乙肝病毒传播的风险较低[35,36]。

为了将乙肝病毒传播的风险降到最低,对于即将接受骨髓或实体器官捐赠的受者,如果器官捐献者存在OBI,医生通常会给受者开处方进行抗病毒预防。此外,即使抗-HBc阳性的捐赠者血液中无法检测到HBVDNA,许多治疗中心扔提倡对接受器官移植者使用核苷类似物加以预防。

OBI和慢性肝病的关系

早在20世纪80年代初,已经发现HBsAg阴性的慢性肝病患者体内存在HBVDNA[37,38]。一项meta分析研究显示,OBI导致慢性肝病的OR值为8.9[39]。目前已经有不同的方法来评估OBI的临床病理作用,就是依靠检查肝脏生化参数和肝脏组织学活动进行的研究。一般而言,大多数OBI患者肝脏生化正常,肝脏组织学上极少出现或不发生坏死炎症和纤维化[22,40-42]。然而,OBI患者仍有极大风险发展为肝硬化和肝细胞癌。在不明原因的肝硬化患者中,也发现4.8-40%的患者同时存在OBI[6,43-45]。

首次开展研究OBI在慢性肝病中的作用是在慢性丙型肝炎病毒(HCV)感染患者中进行的。有许多研究证明,OBI合并慢性HCV感染是患者发生肝硬化和肝癌的病原学病因之一[37,46-52]。有研究表明,伴有OBI的慢性丙肝患者的纤维化期比没有OBI的患者更严重[53]。据一项研究表明,在66例有OBI的慢性HCV患者中,33%的患者会发展为肝硬化;而没有OBI的慢性HCV患者只有19%的患者会发展为肝硬化(P=0.04)[46]。关于OBI慢性HCV患者发生肝细胞癌的风险,有多项研究表明,抗-HBc阳性(HR1.6-3)和HBVDNA阳性是这些患者发生肝细胞癌的独立危险因素[51,53,54]。这表明,OBI可能与慢性HCV感染患者肝病的进展程度有密切关系。然而,无OBI的慢性HCV患者和有OBI的慢性HCV患者相比,一些研究并没有观察到后者在疾病严重程度、病程进展速度以及发生肝细胞癌的风险明显增加[55-59]。一项包括12项研究的荟萃分析显示,OBI增加了HR为2.8[52]的慢性HCV患者发展为肝细胞癌的风险。从所有研究的结果来看,OBI似乎可以增加慢性HCV患者的疾病进展和肝细胞癌发展的机会,然而,这可能需要更多的大规模前瞻性研究来证实这一观点。

20世纪80年代,两项重大研究证实了HBsAg阴性的肝细胞癌患者肝脏中存在HBVDNA[60,61]。随后,其他几个病例队列研究表明,45-80%的不明原因肝癌患者肝脏中携带乙肝病毒。针对不同HBV基因区域的PCR可以检测到HBVDNA[6,62],在非肿瘤组织中扩增产物相对高于肿瘤组织,在X基因中相对高于其他基因[63]。研究还表明,肝脏中的HBVDNA以游离或结合形式存在[6,62]。基因的克隆整合状态常见于肝细胞癌[64]。根据两项研究,48%和73%的隐源性肝细胞癌患者可以确定患有OBI[63,65]。另一项研究表明,OBI是肝癌发生的独立因素,相对危险度为8.25[54]。这些研究表明,OBI与肝细胞癌风险程度的增加相关[6,63,65,66],日本进行的一项纵向随访研究证实了这种关联[67]。16项研究放在一起进行分析可以得出结论,OBI增加了发生肝细胞癌的风险。5项前瞻性研究[52]的调整优势比为2.9。另一项包括14项研究的meta分析也显示,OBI受试者患肝细胞癌的风险比无OBI受试者高8.9倍[39]。

有几种假说解释了OBI的致癌特性。首先,OBI可能存在低级别炎症,进而导致或加重肝硬化[11,12];其次,OBI的HBV基因组具有致癌潜力,它可能整合到人类基因组或以游离状态存在[6,60,61,68-71];第三,OBI可能仍然具有HBV转录活性,这与具有转化性质的病毒蛋白合成(如X蛋白和剪接的preS-S蛋白)有关[72]。

OBI的HBV再激活

在接受免疫抑制治疗的HBsAg阳性患者中,HBV再激活的机理已经得到很好的阐述,并被越来越多的人所认知[73]。HBV再激活的识别在临床上非常重要,因为如果不及时治疗,可能会发展为致命的肝脏失代偿病变。根据两项研究显示,468例HBsAg阴性患者和131例抗-HBc阳性患者同时接受抗肿瘤坏死因子治疗,HBV再激活率分别为1.7%和0%[74,75]。在另一项围绕80例HBsAg阴性患者开展的研究中,34例接受化疗的抗HBc阴性患者(76例)未观察到HBV再激活。在46例抗-HBc阳性患者中,21例接受环磷酰胺、阿霉素、长春新碱、泼尼松龙(CHOP)联合美罗华治疗的患者中,有5例(23.8%)患者乙肝病毒发生再激活,其中1例患者死亡;其余25例抗-HBc阳性患者接受泼尼松龙治疗而未使用美罗华的情况下,则未发生HBV再激活。一项前瞻性研究显示,接受美罗华治疗的HBsAg阴性和抗-HBc阳性患者中,有41.5%的患者会发生HBV再激活[77]。抗-HBs阳性者HBV再激活率(34.4%)明显低于抗-HBs阴性者(68.3%,P=0.012)。在OBI受试者中,B细胞消耗剂(如美罗华)的使用大大提高了HBV再激活的风险。

另一组接受造血干细胞移植(HSCT)的OBI患者也承担着相当大的风险,因为他们处于长期的免疫抑制状态,有可能导致乙肝病毒再激活。另外有研究表明,HBsAg阴性、抗-HBc阳性的造血干细胞移植受者的HBV再激活率在2.7%-42.9%[78-80]之间。从最近的一项前瞻性研究来看,2年的累积HBV再激活率为35%[81]。50岁以上患者(HR7.9)和慢性移植物抗宿主病(GVHD)患者(HR7.6)是导致HBV再激活的独立原因。

在接受免疫抑制治疗的OBI受试者中发现,有几种机制可能导致HBV再激活。第一,由于HBV基因组中含有糖皮质激素反应元件,免疫抑制剂或化疗药物可能直接增强HBV复制,特别是应用含有类固醇方案的药物时;第二,抑制B细胞和T细胞功能的同时,也降低了机体对病毒复制的免疫监视;第三,停用免疫抑制治疗后,免疫活性的反弹可能对高HBV载量的肝细胞造成严重的细胞介导损伤。

目前,乙肝表面抗原阳性患者在接受免疫抑制治疗时,推荐使用常规预防性抗病毒药物。一般建议对HBsAg阴性、抗-HBc/抗-HBs可阴可阳、HBVDNA阳性且准备接受免疫抑制治疗/造血干细胞移植的患者进行预防性抗病毒治疗。对于检测不到HBVDNA的患者,在对其停止免疫抑制治疗后至少12个月内应定期监测,间隔期1-3个月,目前缺乏间隔期监测的数据。然而,监测频率应取决于所使用药物的类型(例如,服用美罗华的患者应更频繁地接受检查)。证明HBV再激活的最早标记物是HBVDNA。最近,研究发现了两种新的HBV血清学检测方法,一种方法是采用高灵敏度一步化学发光酶免疫分析法结合免疫复合物转移技术(ICT-CLEIA)测定HBsAg(Sysmex公司,日本神户);另一种方法是使用lumipulse公司的化学发光技术测定乙肝核心相关抗原(HBcAg),G1200自动分析仪(Fujirebio公司,日本东京)已被应用于研究预测OBI患者中是否发生HBV再激活[82,83],这两种方法在预测HBV再激活方面都有极高的应用价值。现在还没有足够的数据证明,但是推荐一旦检测到HBVDNA就立即进行抗病毒治疗,而不要等到丙氨酸转氨酶(ALT)升高再接受治疗[84]。类核苷药物在控制HBV再激活方面非常有效,效果也很好。在临床无法常规HBVDNA监测时,有人建议患者也应该优先接受抗病毒治疗[85]。

由于缺乏前瞻性研究,针对OBI患者接受免疫抑制治疗后继发HBV再激活的治疗标准和治疗方案仍有待开发。最近研究表明,HBsAg阴性、抗-HBc阳性患者接受美罗华治疗或造血干细胞的移植过程中,应给予4周的HBVDNA监测,一旦检测到HBVDNA,立即给予恩替卡韦治疗,所有患者均得到良好的控制,无肝炎发作[77,81]。然而,目前还没有研究对不同方案的成本效益进行对比分析。

Acknowledgments

Funding: MF Yuen received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis and Gilead Sciences.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: MFY received speaker fee from GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis and Gilead Sciences; and received research funding and is an advisory board member of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis and Gilead Sciences. MFY serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Blood from Dec 2016 to Dec 2019.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Yamamoto K, Horikita M, Tsuda F, et al. Naturally occurring escape mutants of hepatitis B virus with various mutations in the S gene in carriers seropositive for antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen. J Virol 1994;68:2671-6. [PubMed]

- Hou J, Karayiannis P, Waters J, et al. A unique insertion in the S gene of surface antigen--negative hepatitis B virus Chinese carriers. Hepatology 1995;21:273-8. [PubMed]

- Carman WF, Van Deursen FJ, Mimms LT, et al. The prevalence of surface antigen variants of hepatitis B virus in Papua New Guinea, South Africa, and Sardinia. Hepatology 1997;26:1658-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pollicino T, Raffa G, Costantino L, et al. Molecular and functional analysis of occult hepatitis B virus isolates from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2007;45:277-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang FY, Wong DK, Seto WK, et al. Sequence variations of full-length hepatitis B virus genomes in Chinese patients with HBsAg-negative hepatitis B infection. PLoS One 2014;9:e99028 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, et al. Hepatitis B virus maintains its pro-oncogenic properties in the case of occult HBV infection. Gastroenterology 2004;126:102-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai CL, Ratziu V, Yuen MF, et al. Viral hepatitis B. Lancet 2003;362:2089-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michalak TI, Pasquinelli C, Guilhot S, et al. Hepatitis B virus persistence after recovery from acute viral hepatitis. J Clin Invest 1994;93:230-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yotsuyanagi H, Yasuda K, Iino S, et al. Persistent viremia after recovery from self-limited acute hepatitis B. Hepatology 1998;27:1377-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penna A, Artini M, Cavalli A, et al. Long-lasting memory T cell responses following self-limited acute hepatitis B. J Clin Invest 1996;98:1185-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bläckberg J, Kidd-Ljunggren K. Occult hepatitis B virus after acute self-limited infection persisting for 30 years without sequence variation. J Hepatol 2000;33:992-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuki N, Nagaoka T, Yamashiro M, et al. Long-term histologic and virologic outcomes of acute self-limited hepatitis B. Hepatology 2003;37:1172-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mulrooney-Cousins PM, Michalak TI. Persistent occult hepatitis B virus infection: experimental findings and clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:5682-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai CL, Yuen MF. Occult hepatitis B infection: Incidence, detection and clinical implications. ISBT Science Series 2009;4:347-51. [Crossref]

- Yuen MF, Wong DK, Fung J, et al. HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in Asian patients: replicative level and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1192-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn SH, Park YN, Park JY, et al. Long-term clinical and histological outcomes in patients with spontaneous hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance. J Hepatol 2005;42:188-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhns M, McNamara A, Mason A, et al. Serum and liver hepatitis B virus DNA in chronic hepatitis B after sustained loss of surface antigen. Gastroenterology 1992;103:1649-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuen MF, Wong DK, Sablon E, et al. HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in the Chinese: virological, histological, and clinical aspects. Hepatology 2004;39:1694-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen YC, Sheen IS, Chu CM, et al. Prognosis following spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B patients with or without concurrent infection. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1084-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huo TI, Wu JC, Lee PC, et al. Sero-clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen in chronic carriers does not necessarily imply a good prognosis. Hepatology 1998;28:231-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuen MF, Ahn SH, Chen DS, et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Disease revisit and management recommendations. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50:286-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong DK, Fung J, Lee CK, et al. Intrahepatic hepatitis B virus replication and liver histology in subjects with occult hepatitis B infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22:290.e1-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Komiya Y, Katayama K, Yugi H, et al. Minimum infectious dose of hepatitis B virus in chimpanzees and difference in the dynamics of viremia between genotype A and genotype C. Transfusion 2008;48:286-94. [PubMed]

- Yuen MF, Wong DK, Lee CK, et al. Transmissibility of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection through blood transfusion from blood donors with occult HBV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:624-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Candotti D, Allain JP. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2009;51:798-809. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosley JW, Stevens CE, Aach RD, et al. Donor screening for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen and hepatitis B virus infection in transfusion recipients. Transfusion 1995;35:5-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Satake M, Taira R, Yugi H, et al. Infectivity of blood components with low hepatitis B virus DNA levels identified in a lookback program. Transfusion 2007;47:1197-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB, Bales ZB, et al. Type B hepatitis after transfusion with blood containing antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. N Engl J Med 1978;298:1379-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lander JJ, Gitnick GL, Gelb LH, et al. Anticore antibody screening of transfused blood. Ox. Vox Sang 1978;34:77-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koziol DE, Holland PV, Alling DW. Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen as a paradoxical marker for non-A, non-B hepatitis agents in donated blood. Ann Intern Med 1986;104:488-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raimondo G, Caccamo G, Filomia R, et al. Occult HBV infection. Semin Immunopathol 2013;35:39-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chemin I, Guillaud O, Queyron PC, et al. Close monitoring of serum HBV DNA levels and liver enzymes levels is most useful in the management of patients with occult HBV infection. J Hepatol 2009;51:824-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dickson RC, Everhart JE, Lake JR, et al. Transmission of hepatitis B by transplantation of livers from donors positive for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Liver Transplantation Database. Gastroenterology 1997;113:1668-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muñoz SJ. Use of hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2002;8:S82-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wachs ME, Amend WJ, Ascher NL, et al. The risk of transmission of hepatitis B from HBsAg(-), HBcAb(+), HBIgM(-) organ donors. Transplantation 1995;59:230-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Feo TM, Poli F, Mozzi F, et al. Risk of transmission of hepatitis B virus from anti-HBC positive cadaveric organ donors: a collaborative study. Transplant Proc 2005;37:1238-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bréchot C, Degos F, Lugassy C, et al. Hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with chronic liver disease and negative tests for hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med 1985;312:270-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brechot C, Hadchouel M, Scotto J, et al. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA in liver and serum: a direct appraisal of the chronic carrier state. Lancet 1981;2:765-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Covolo L, Pollicino T, Raimondo G, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus and the risk for chronic liver disease: a meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2013;45:238-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuen MF, Lee CK, Wong DK, et al. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B infection in a highly endemic area for chronic hepatitis B: a study of a large blood donor population. Gut 2010;59:1389-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fung J, Lai CL, Chan SC, et al. Correlation of liver stiffness and histological features in healthy persons and in patients with occult hepatitis B, chronic active hepatitis B, or hepatitis B cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1116-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong DK, Fung J, Lee CK, et al. Hepatitis B virus serological and virological activities in blood donors with occult hepatitis B. Hepatol Int 2014;8:S149.

- Hou J, Wang Z, Cheng J, et al. Prevalence of naturally occurring surface gene variants of hepatitis B virus in nonimmunized surface antigen-negative Chinese carriers. Hepatology 2001;34:1027-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bréchot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D, et al. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely “occult”? Hepatology 2001;34:194-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alavian SM, Miri SM, Hollinger FB, et al. Occult Hepatitis B (OBH) in Clinical Settings. Hepat Mon 2012;12:e6126 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med 1999;341:22-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Niigaki M, et al. Serologically silent hepatitis B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significance. J Med Virol 1999;58:201-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tanaka T, Inoue K, Hayashi Y, et al. Virological significance of low-level hepatitis B virus infection in patients with hepatitis C virus associated liver disease. J Med Virol 2004;72:223-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Squadrito G, Pollicino T, Cacciola I, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection is associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients. Cancer 2006;106:1326-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shetty K, Hussain M, Nei L, et al. Prevalence and significance of occult hepatitis B in a liver transplant population with chronic hepatitis C. Liver Transpl 2008;14:534-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adachi S, Shibuya A, Miura Y, et al. Impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection and prior hepatitis B virus infection on development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008;43:849-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi Y, Wu YH, Wu W, et al. Association between occult hepatitis B infection and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Liver Int 2012;32:231-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka S, Nirei K, Tamura A, et al. Influence of occult hepatitis B virus coinfection on the incidence of fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C. Intervirology 2008;51:352-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ikeda K, Marusawa H, Osaki Y, et al. Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen and risk for hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:649-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sagnelli E, Imparato M, Coppola N, et al. Diagnosis and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B infection in patients with biopsy proven chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter study. J Med Virol 2008;80:1547-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:4068-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsubouchi N, Uto H, Kumagai K, et al. Impact of antibody to hepatitis B core antigen on the clinical course of hepatitis C virus carriers in a hyperendemic area in Japan: A community-based cohort study. Hepatol Res 2013;43:1130-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen HY, Su TH, Tseng TC, et al. Impact of occult hepatitis B on the clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: A 10-year follow-up. J Formos Med Assoc 2016; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho J, Lee SS, Choi YS, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection is not associated with disease progression of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:9427-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bréchot C, Hadchouel M, Scotto J, et al. State of hepatitis B virus DNA in hepatocytes of patients with hepatitis B surface antigen-positive and -negative liver diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1981;78:3906-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shafritz DA, Shouval D, Sherman HI, et al. Integration of hepatitis B virus DNA into the genome of liver cells in chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Studies in percutaneous liver biopsies and post-mortem tissue specimens. N Engl J Med 1981;305:1067-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paterlini P, Gerken G, Nakajima E, et al. Polymerase chain reaction to detect hepatitis B virus DNA and RNA sequences in primary liver cancers from patients negative for hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med 1990;323:80-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong DK, Huang FY, Lai CL, et al. Occult hepatitis B infection and HBV replicative activity in patients with cryptogenic cause of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2011;54:829-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brechot C, Pourcel C, Louise A, et al. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA sequences in human hepatocellular carcinoma in an integrated form. Prog Med Virol 1981;27:99-102. [PubMed]

- Yotsuyanagi H, Shintani Y, Moriya K, et al. Virologic analysis of non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: frequent involvement of hepatitis B virus. J Infect Dis 2000;181:1920-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fang Y, Shang QL, Liu JY, et al. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection among hepatopathy patients and healthy people in China. J Infect 2009;58:383-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ikeda K, Kobayashi M, Someya T, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection increases hepatocellular carcinogenesis by eight times in patients with non-B, non-C liver cirrhosis: a cohort study. J Viral Hepat 2009;16:437-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tamori A, Nishiguchi S, Kubo S, et al. Possible contribution to hepatocarcinogenesis of X transcript of hepatitis B virus in Japanese patients with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 1999;29:1429-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paterlini P, Poussin K, Kew M, et al. Selective accumulation of the X transcript of hepatitis B virus in patients negative for hepatitis B surface antigen with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 1995;21:313-21. [PubMed]

- Bréchot C, Gozuacik D, Murakami Y, et al. Molecular bases for the development of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Semin Cancer Biol 2000;10:211-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saitta C, Tripodi G, Barbera A, et al. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA integration in patients with occult HBV infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int 2015;35:2311-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cougot D, Neuveut C, Buendia MA. HBV induced carcinogenesis. J Clin Virol 2005;34:S75-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuen MF. Need to improve awareness and management of hepatitis B reactivation in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Hepatol Int 2016;10:102-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee YH, Bae SC, Song GG. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in rheumatic patients with hepatitis core antigen (HBV occult carriers) undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013;31:118-21. [PubMed]

- Giannitti C, Lopalco G, Vitale A, et al. Long-term safety of anti-TNF agents on the liver of patients with spondyloarthritis and potential occult hepatitis B viral infection: an observational multicentre study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:93-97. [PubMed]

- Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:605-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seto WK, Chan TS, Hwang YY, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with prior HBV exposure undergoing rituximab-containing chemotherapy for lymphoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3736-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Viganò M, Vener C, Lampertico P, et al. Risk of hepatitis B surface antigen seroreversion after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:125-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammond SP, Borchelt AM, Ukomadu C, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15:1049-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto S, Kanda T, Nakaseko C, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients in Japan: efficacy of nucleos(t)ide analogues for prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:21455-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seto WK, Chan TS, Hwang YY, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in occult viral carriers undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a prospective study. Hepatology 2017;65:1451-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seto WK, Wong DH, Chan TY, et al. Association of hepatitis B core-related antigen with hepatitis B virus reactivation in occult viral carriers undergoing high-risk immunosuppressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1788-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shinkai N, Kusumoto S, Murakami S, et al. Novel monitoring of hepatitis B reactivation based on ultra-high sensitive hepatitis B surface antigen assay. Liver Int 2017; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2012;57:167-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marzano A, Angelucci E, Andreone P, et al. Prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39:397-408. [Crossref] [PubMed]

蒋祺

河南大学医学院免疫学硕士研究生学历,输血技术中级职称,开封市检验协会委员,2015年至今任核酸实验室主任。长期从事血液分子生物学研究,研究生期间参与2项国家自然科学基金研究工作。2016年,在中国医师协会和输血医师分会联合举办的“迎接新常态,勇做输血领军人”全国人才选拔活动中,入选“全国输血医学人才库”。在国家级刊物中发表多篇学术论文。(更新时间:2021/8/26)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Yuen MF. Clinical implication of occult hepatitis B infection. Ann Blood 2017;2:5.