免疫介导血小板减少症的实验室检查

前言

血小板在止血和炎症反应中发挥着重要的作用,近来它也被证实参与了先天和后天适应性的免疫反应[1,2]。除了表达ABO血型抗原和人类白细胞抗原(HLA)-Ⅰ这类非血小板特异性抗原外,人类血小板表面还表达人类血小板抗原(HPA)。迄今为止,已鉴定出6个血小板膜糖蛋白(GPIa, GPIbα, GPIbβ, GPIIb, GPIIIa 和 CD109)上的29个HPA系统。其中,12个被列为6个双等位基因系统(HPA-1, -2, -3, -4, -5和 -15)(参考免疫多态性数据库,http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/hpa/)。HPAs按照被发现的先后顺序编号,并按从高到低的频率予以命名相应的字母[3]。除了一个特征性的HPAs外,所有HPA都代表单核苷酸多态性及其所致的单一氨基酸替代。大多数HPAs位于GPIIb/IIIa上 [4]。HPA变异频率因人群而异,因此不同的人群具有不同的HPA,具有一定人群相特异性。在白种人中,抗HPA-1a同种抗体是免疫介导血小板减少症的主要原因,而在亚洲人特别是日本人中,HPA-4 和 Naka(抗-CD36)抗体则是主要的成分[5]。不相容妊娠、输血或者更罕见的器官移植可诱发抗HPA同种抗体产生,而后者参与了免疫介导的血小板减少症的发病机制,包括胎儿/新生儿同种免疫血小板减少症(FNAIT)、难治性血小板输注(PTR)和输血后紫癜(PTP)。FNAIT的发病机制类似于新生儿溶血(HDN),胎儿遗传了父亲的不相容抗原并在细胞表面表达,母亲则产生了针对这种不相容抗原的同种抗体[6]。IgG型的母体同种抗体能通过胎盘与胎儿血小板结合。抗体结合的血小板在循环中被巨噬细胞清除,导致血小板减少。FNAIT的临床表现多样,包括从偶发的轻度血小板减少到致命性颅内出血及神经系统后遗症等[7]。

PTR被定义为对至少连续2次血小板输注反应不佳。PTR患者由于反复输血产生抗血小板抗体导致血小板提升不明显[8,9]。参与PTR免疫反应最常见的同种抗体是抗HLA-Ⅰ类抗体(约80-90%),其次为抗-HPA抗体(约10-20%)[10,11]。虽然输注血小板有助于预防出血并发症,但化疗或造血干细胞移植期间发生PTR可增加出血风险并危及患者生命。因此,致病性抗体的检测和鉴别对于免疫介导的血小板减少症的诊断、预防和管理至关重要。本文将描述目前可用的检测抗血小板抗体的方法,并讨论每种方法的优缺点。

经典方法

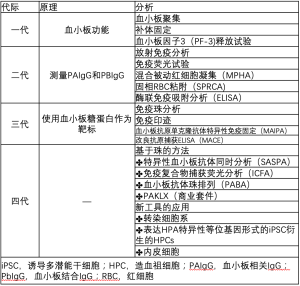

目前已开展了多种技术用于免疫性血小板疾病的血清学检测(表1),如血小板聚集分析、血小板因子3(PF-3)释放试验和血清素释放试验等早期检测技术,都是基于血小板功能进行检测[12,13]。然而,由于仅部分抗体可诱发血小板活化,而大部分并不能激活血小板,因此这些方法的敏感性很低。此后,便出现了识别完整血小板的结合分析法,包括血小板免疫荧光试验(PIFT)和混合被动血凝试验(MPHA)。但是,这些分析对血小板特异性抗原和非特异性抗原很难鉴别。1980年代,由于GP特异性抗体的成功研发,出现了新的抗原捕获分析方法,如抗原捕获ELISA(ACE)、改良抗原捕获ELISA(MACE)和血小板抗原单克隆抗体特异性免疫固定(MAIPA)。这些抗原捕获分析可以鉴别特异性GPs的抗原表位。

Full table

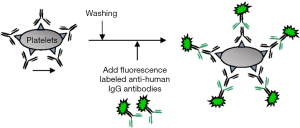

PIFT

PIFT检测是通过完整血小板与患者或对照者的血清共同孵育,再与抗原表位相结合,然后加入荧光标记的抗人IgG/IgM作为二抗,并让其与已结合抗原表位的抗体相结合,这样就可以用荧光显微镜或流式细胞仪分析荧光标记的血小板(图1)。荧光显微镜最初时被用于评估染色血小板的荧光强度,但缺乏客观性;而流式细胞仪检测荧光强度更具有客观性,检测结果可定量反映样本荧光强度与阴性对照的比率,因此荧光显微镜逐渐被流式细胞仪所代替[14]。流式细胞仪法是检测完整血小板的一种应用广泛的技术,对抗-HPA抗体高度敏感,但HPA-5和HPA-15由于血小板表面表达很少,因此敏感性很低。在血小板表面,约有3000-5000个HPA-5的抗原位点,而HPA-15位点只有1000个[4]。对于低表达的这类抗原,流式细胞仪也难以检测。结合分析法则存在多种抗体鉴别困难的缺点,尤其是抗-HLA和抗-HPA抗体同时存在时更明显。为了消除抗-HLA抗体的反应,使用氯喹或者酸预处理血小板,即可破坏血小板表面的β2 微球蛋白。如果血清中同时存在高滴度抗-HLA抗体,要完全消除抗-HLA抗体的反应性则非常困难[15,16]。由于抗-A和抗-B抗体也能被检测到,因此需选择O型血小板进行检测。

MPHA和磁性MPHA

MPHA试验是先将完整的血小板或血小板膜提取物包被涂于圆底的微孔板上,再将人抗血清加入微孔与血小板抗原结合[17-19]。为了检测反应强度,由绵羊红细胞(MPHA)或磁珠(M-MPHA)构成的、涂有抗人IgG的指示细胞加入到微孔中自然沉淀(MPHA)或用磁盘加速(M-MPHA)。如图2所示,如果存在抗血小板抗体,将与固定在微孔底部的相应抗原结合,并被指示细胞表面的抗人IgG所识别。如果呈阳性反应,指示细胞将与已结合特异性抗原的人IgG相结合,保持分散状态而不出现沉淀;如果呈阴性反应,指示细胞沉淀到微孔底部,形成清晰的环状。判断反应结果时,样品孔需与阴性对照孔图案进行对比。MPHA对包括HPA-5在内的多数HPA抗体具有高度敏感性,在日本主要用于血小板血清学试验。它具有很多优点,包括一次检测可分析多个样品,操作简单和检测时间短,特别是使用磁珠后,抗体与血小板抗原结合后3分钟即发生反应。这种方法也存在缺点,如同时存在高滴度的抗HLA抗体可干扰HPA抗体的鉴别。如PIFT所述,用氯喹或酸预处理可去除HLA-Ⅰ类抗原性,但是这种处理也会破坏HPA-15等部分抗原的抗原性。

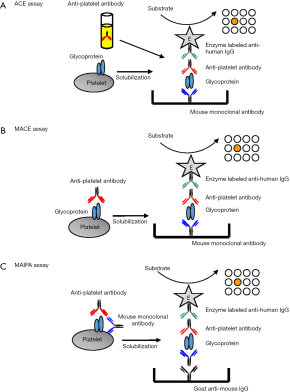

抗原捕获分析

目前有三类抗原捕获分析方法,包括ACE、改良ACE(MACE)和MAIPA[20-22],这些方法中关于糖蛋白抗原的捕获方式不同(图3)。MAIPA在欧洲和其他国家被广泛使用,而MACE在美国则是首选[23,24]。

在MAIPA试验中,血小板被患者的血清致敏、洗涤,再与识别血小板表面的目标糖蛋白的小鼠单克隆抗体一起孵育。血小板被两种抗体致敏后,用Triton之类的非离子洗涤剂进行洗涤与溶解。离心后去除细胞骨架碎片,将由GPs特异性mAb/GPs/抗血小板抗体组成的三分子复合物上清液加入到用羊抗鼠IgG固定的微量滴定板的孔中,被固定的IgG即能捕获复合物。加入过氧化物酶标记的抗人IgG作为合适的底物,即可检测捕获的复合物。这种方法敏感性高,特异性强,是血小板免疫检测方法的金标准。包括MAIPA在内的抗原捕获法可以鉴别HPA抗体与抗HLA抗体。然而,小鼠单克隆抗体的选择很重要,因为部分单克隆抗体可能会与抗-HPA同种抗体,尤其是Naka抗体可竞争与抗原表位相结合 [25],故不适合作为筛选测试。由于检测时间长,且需要多个微孔板和大量HPA型血小板来识别与位于所有主要GP上的HPA反应的抗体,不同实验室对MAIPA方案和试剂进行了改良。因此,实验室间检测HPA抗体的灵敏度存在差异[26,27]。

检测HPA抗体的新方法

基于微珠的技术

近来研发了几种敏感高和高通量的不同微珠技术。由于抗HPA-1a抗体与白种人相关性最强,因此报道的微球技术分析法主要为HPA-1a抗体的检测[28-30]。微珠技术的最大优势是可以同时检测同一个试管或微孔中存在的多个抗体。此外,这种方法具有检测时间短、速度快的优点。这些微珠技术应用于HLA抗体检测时,还可检测到临床少见或机体自然产生的抗体存在,这与使用的重组HLA抗原密切相关[35,36]。目前,没有证据支持这些技术用于检测抗HPA抗体。

免疫复合物捕获荧光分析(ICFA)

ICFA是一种基于Luminex技术与抗原捕获法相结合的方法[32]。血小板被患者的血清致敏、洗涤后,再用非离子洗涤剂溶解,过程类似于MACE分析法。然后将离心后的上清裂解液与GP特异性鼠单克隆抗体耦合的聚苯乙烯珠共同孵育,以替代MACE中的微量滴定板。将微珠洗涤后再与PE耦合的山羊抗人IgG抗体共同孵育,清洗后用Luminex(Luminex Co, Austin, TX, USA)系统读珠(图4)。这种方法需要检测一定数量的供者血小板来检测HPA和HLA抗体,但比经典方法的体积要少。对HPA-1a、-2b、-3a、-3b、-4a、-4b、-5a -5b、 -6b和 Naka 抗体的检测,在以往的临床报道中被得到证实。由于缺乏相应的抗血清,故ICFA并不能检测HPA-15 抗体[32]。血小板抗体珠阵列(PABA)也是应用类似的方法,检测HPA-15b同种抗体[37]。分别测试了表达重组CD109蛋白的细胞系以及新鲜和冷冻的HPA-15 型血小板,发现只有细胞系和新鲜血小板能够识别HPA-15b抗体。由于ICFA是以抗原捕获分析作为基础,因此捕获单克隆抗体的选择对于防止假阴性反应至关重要。

PAKLx

PAKLx(Lifecodes, HOROGIC/Genprobe)是一种检测和鉴别抗血小板抗体的微球检测方法。该试剂盒中,来自HPA型血小板供体的纯化GP和来自汇集血小板的HLA I类抗原(由 100 名白种人、100 名非裔美国人和 100 名西班牙裔献血者组成)固定在聚苯乙烯珠上。微珠用患者血清致敏、洗涤,然后将珠子与PE标记的抗人IgG抗体一起孵育,并使用Luminex设备测量珠子的平均荧光强度 (MFI)。将每个样品珠的MFI与阴性对照珠的MFI 进行比较,并将结果判断为阴性或阳性。目前可以检测HPA-1a、 -1b、-2a、-2b、-3a、-3b、-4a、-4b、-5a、-5b和Naka 抗体,但不能检测抗HPA-15a和-15b抗体,是由于试剂盒中没有提供HPA-15抗体鉴别微珠。临床上,抗HPA-15抗体在NAIT和PTR中十分重要,因此非常需要包括抗HPA-15抗体检测在内的珠分析。由于操作简便,不需要特殊的技能,它是一种很好的筛选方法。此外,该检测不需要HPA型血小板,只需要少量的血清,具有很高的敏感性。缺点是不能检测抗HPA-3a与-5b抗体等部分抗体,其中抗HPA-3a只能应用相应的单克隆抗体采用PIFT和MAIPA方法才能检测,以及-5b抗体[33]。此外,该方法不能检测低滴度和低亲和力抗体,因此需要和其他方法结合使用。

转染细胞系,诱导多能造血干细胞(iPSC)衍生、表达HPA等位基因特异性的造血祖细胞(HPCs)和内皮细胞(ECs)

血小板同种抗体实验室诊断的难点是难以获得合适的血小板,尤其是低表达HPA抗原的血小板。

近十年来,表达HPAs的转染后的中国仓鼠卵巢细胞系(CHO)已经产生。MAIPA验证了这些细胞系的有效性,但是经过一段时间后这些细胞的HPAs表达水平明显减少[28,29]。近来研发了不表达HLA或HPA的K562转染细胞的HPA面板。这种具有HPA抗体的细胞的反应既有敏感性又有特异性,已证实与正常人血清不发生反应。到目前为止,已经生产出了HPA-1a、-1b、-2a、-2b、-3b、-4b、-5b、-6b、-7b、-7variant、-12a、-13b、-15a、-15b、-18b、-21b、和CD36的转染细胞系。转染细胞对于检测和鉴别HPA抗体非常重要,可以鉴别包含HLA抗体的样品中的HPA抗体的单一特异性,而这种情况在PIFT和MPHA方法中却难以鉴别。

最近,密尔沃基的研究小组报道使用CRISPR/Cas9基因编辑技术(聚簇有规律间隔的短回文重复序列/CRISPR相关蛋白9)从巨核样DAMI细胞中成功的产生出多潜能干细胞(iPSC)[41]。他们能够生产表达HPA-1b同种抗原表位的细胞,HPA-1b是一种HPA-1的低频抗原。这种设计的血小板可用于与血小板同种抗体相关的临床疾病的诊断、研究和完全治愈,是一种很有前景的技术。

此外,GPIIIa (整合素β3)可能是抗HPA同种抗体的重要靶标,其与整合素alpha v(αvβ3)形成复合物的形式存在于ECs。同种抗体与αvβ3的反应在颅内出血(ICH)中起重要作用,这是FNAIT的严重并发症[41,43]。不针对GPIbα的抗β3整合素抗体在FNAIT模型中减少了大脑和视网膜血管密度。在FNAIT模型中,针对β3整联蛋白而非GPIbα的抗体会降低大脑和视网膜血管密度,削弱血管生成信号并增加EC细胞凋亡[42]。使用伴或不伴ICH的FNAIT母亲的血清样本,已证实抗HPA-1a抗体对抗αvβ3的特异性在伴ICH的那些FNAIT患者中是存在的,半胱天冬酶-3/7活化后,这些抗体诱导HPA-1a阳性的EC凋亡,由活性氧介导并干扰EC对玻连蛋白的粘附和EC小管的形成[43]。鉴定具有抗αvβ3特异性的同种抗体可能有助于确定FNAIT的严重病例,并有助于实施早期和更积极的预防措施。所有这些细胞系不仅可用于包括MAIPA、MACE和免疫荧光试验的经典方法,还可应用于如ICFA这样的新技术,为免疫性血小板减少症的诊断提供了新的方法。将ECs作为靶标使用对于诊断重症FNAIT病例,尤其是ICH相关的病例非常重要。

结论

检测抗血小板抗体的新方法已得到验证。然而,由于用于验证测试的血清样本数量有限,以及抗体特异性,经典方法和新方法之间存在一些差异,因此需要进一步研究以验证这些新技术。现有技术大多数主要检测MPAs的同种抗体。但是一些抗体检测,如抗HPA-3还存在问题。以前报道提示,HPA-3表位存在不同的结构要求,只有用完整血小板才能检测到一些抗体,而不能使用微珠技术[33,44,45]。此外,据德国和密尔沃基的研究组报道,在重症FNAIT病例采用表面等离子共振(SPR)检测低亲和力抗HPA-1a抗体,而用MAIPA分析并不能鉴别出来[46,47]。最近报道显示,低亲和力抗HPA-1a抗体大量存在于母亲血清中,以前用MAIPA分析也检测不到这些抗体[47,48]。由于血小板膜糖蛋白携带有血小板同种抗原决定簇和这些同种抗体性质的复杂性,现在单独一种技术不足以检测到全部临床相关抗体。近几年发现了很多低频HPAs[49],将来还可能发现新的HPA抗原。在应用新的微珠技术前,针对新或低频HPA抗原、只在完整血小板上形成的构象依赖性抗原决定簇或内皮特异性表位的同种抗体就有可能被忽略了。虽然血小板血清学取得了明显的进展,但进一步完善血小板抗体检测技术时,需要考虑各种方法的优点和缺点。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Sentot Santoso) for the series “Platelet Immunology” published in Annals of Blood. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aob.2018.09.02). The series “Platelet Immunology” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. Nelson Hirokazu Tsuno serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Blood from March 2018 to March 2020. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the manuscript and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr, Freedman J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:264-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrell CN, Aggrey AA, Chapman LM, et al. Emerging roles for platelets as immune and inflammatory cells. Blood 2014;123:2759-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe P, Watkins NA, Ouwehand WH, et al. Nomenclature of human platelet antigens. Vox Sang 2003;85:240-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtis BR, McFarland JG. Human platelet antigens - 2013. Vox Sang 2014;106:93-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuno NH, Matsuhashi M, Iino J, et al. The importance of platelet antigens and antibodies in immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia. ISBT Science Sereis 2014;9:104-11. [Crossref]

- Serrarens-Janssen VM, Semmekrot BA, Novotny VM, et al. Fetal/neonatal allo-immune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT): past, present, and future. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2008;63:239-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Risson DC, Davies MW, Williams BA. Review of neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. J Paediatr Child Health 2012;48:816-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Friedberg RC, Mintz PD. Causes of refractoriness to platelet transfusion. Curr Opin Hematol 1995;2:493-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hod E, Schwartz J. Platelet transfusion refractoriness. Br J Haematol 2008;142:348-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavenski K, Freedman J, Semple JW. HLA alloimmunization against platelet transfusions: pathophysiology, significance, prevention and management. Tissue Antigens 2012;79:237-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trial to Reduce Alloimmunization to Platelets Study Group. Leukocyte reduction and ultraviolet B irradiation of platelets to prevent alloimmunization and refractoriness to platelet transfusions. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1861-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warner M, Kelton JG. Laboratory investigation of immune thrombocytopenia. J Clin Pathol 1997;50:5-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McFarland JG. Detection and identification of platelet antibodies in clinical disorders. Transfus Apher Sci 2003;28:297-305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allen DL, Chapman J, Phillips PK, et al. Sensitivity of the platelet immunofluorescence test (PIFT) and the MAIPA assay for the detection of platelet-reactive alloantibodies: a report on two U.K. National Platelet Workshop exercises. Transfus Med 1994;4:157-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurata Y, Oshida M, Take H, et al. New approach to eliminate HLA class I antigens from platelet surface without cell damage: acid treatment at pH 3.0. Vox Sang 1989;57:199-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurata Y, Oshida M, Take H, et al. Acid treatment of platelets as a simple procedure for distinguishing platelet-specific antibodies from anti-HLA antibodies: comparison with chloroquine treatment. Vox Sang 1990;59:106-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shibata Y, Juji T, Nishizawa Y, et al. Detection of platelet antibodies by a newly developed mixed agglutination with platelets. Vox Sang 1981;41:25-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shibata Y, Matsuda I, Miyaji T, et al. Yuka, a new platelet antigen involved in two cases of neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Vox Sang 1986;50:177-80. [PubMed]

- Shibata Y, Miyaji T, Ichikawa Y, et al. A new platelet antigen system, Yuka/Yukb. Vox Sang 1986;51:334-6. [PubMed]

- Furihata K, Nugent DJ, Bissonette A, et al. On the association of the platelet-specific alloantigen, Pena, with glycoprotein IIIa. Evidence for heterogeneity of glycoprotein IIIa. J Clin Invest 1987;80:1624-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kiefel V, Santoso S, Weisheit M, et al. Monoclonal antibody-specific immobilization of platelet antigens (MAIPA): a new tool for the identification of platelet-reactive antibodies. Blood 1987;70:1722-6. [PubMed]

- Menitove JE, Pereira J, Hoffman R, et al. Cyclic thrombocytopenia of apparent autoimmune etiology. Blood 1989;73:1561-9. [PubMed]

- Davoren A, Curtis BR, Aster RH, et al. Human platelet antigen-specific alloantibodies implicated in 1162 cases of neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Transfusion 2004;44:1220-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghevaert C, Campbell K, Walton J, et al. Management and outcome of 200 cases of fetomaternal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Transfusion 2007;47:901-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morel-Kopp MC, Daviet L, McGregor J, et al. Drawbacks of the MAIPA technique in characterising human antiplatelet antibodies. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1996;7:144-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe P, Allen D, Chapman J, et al. Interlaboratory variation in the detection of clinically significant alloantibodies against human platelet alloantigens. Br J Haematol 1997;97:204-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allen D, Ouwehand WH, de Haas M, et al. Interlaboratory variation in the detection of HPA-specific alloantibodies and in molecular HPA typing. Vox Sang 2007;93:316-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakchoul T, Meyer O, Agaylan A, et al. Rapid detection of HPA-1 alloantibodies by platelet antigens immobilized onto microbeads. Transfusion 2007;47:1363-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skaik Y, Battermann A, Hiller O, et al. Development of a single-antigen magnetic bead assay (SAMBA) for the sensitive detection of HPA-1a alloantibodies using tag-engineered recombinant soluble beta3 integrin. J Immunol Methods 2013;391:72-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chong W, Metcalfe P, Mushens R, et al. Detection of human platelet antigen-1a alloantibodies in cases of fetomaternal alloimmune thrombocytopenia using recombinant beta3 integrin fragments coupled to fluorescently labeled beads. Transfusion 2011;51:1261-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen XD, Dugrillon A, Beck C, et al. A novel method for simultaneous analysis of specific platelet antibodies: SASPA. Br J Haematol 2004;127:552-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara K, Shimano K, Tanaka H, et al. Application of bead array technology to simultaneous detection of human leucocyte antigen and human platelet antigen antibodies. Vox Sang 2009;96:244-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porcelijn L, Huiskes E, Comijs-van Osselen I, et al. A new bead-based human platelet antigen antibodies detection assay versus the monoclonal antibody immobilization of platelet antigens assay. Transfusion 2014;54:1486-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rockenbauer L, Eichelberger B, Panzer S. Comparison of the bead-based simultaneous analysis of specific platelet antibodies assay (SASPA) and Pak Lx Luminex technology with the monoclonal antibody immobilization of platelet antigens assay (MAIPA) to detect platelet alloantibodies. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:1779-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lachmann N, Todorova K, Schulze H, et al. Luminex((R)) and its applications for solid organ transplantation, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and transfusion. Transfus Med Hemother 2013;40:182-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morales-Buenrostro LE, Terasaki PI, Marino-Vázquez LA, et al. "Natural" human leukocyte antigen antibodies found in nonalloimmunized healthy males. Transplantation 2008;86:1111-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metzner K, Bauer J, Ponzi H, et al. Detection and identification of platelet antibodies using a sensitive multiplex assay system-platelet antibody bead array. Transfusion 2017;57:1724-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kroll H, Yates J, Santoso S. Immunization against a low-frequency human platelet alloantigen in fetal alloimmune thrombocytopenia is not a single event: characterization by the combined use of reference DNA and novel allele-specific cell lines expressing recombinant antigens. Transfusion 2005;45:353-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santoso S, Tsuno NH. Progress and challenges in platelet serology. ISBT Science Sereis 2015;10:211-8. [Crossref]

- Hayashi T, Hirayama F. Advances in alloimmune thrombocytopenia: perspectives on current concepts of human platelet antigens, antibody detection strategies, and genotyping. Blood Transfus 2015;13:380-90. [PubMed]

- Zhang N, Zhi H, Curtis BR, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated conversion of human platelet alloantigen allotypes. Blood 2016;127:675-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yougbare I, Lang S, Yang H, et al. Maternal anti-platelet beta3 integrins impair angiogenesis and cause intracranial hemorrhage. J Clin Invest 2015;125:1545-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santoso S, Wihadmadyatami H, Bakchoul T, et al. Antiendothelial αvβ3 Antibodies Are a Major Cause of Intracranial Bleeding in Fetal/Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016;36:1517-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin M, Shieh SH, Liang DC, et al. Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia in Taiwan due to an antibody against a labile component of HPA-3a (Baka). Vox Sang 1995;69:336-40. [PubMed]

- Kataoka S, Kobayashi H, Chiba K, et al. Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia due to an antibody against a labile component of human platelet antigen-3b (Bakb). Transfus Med 2004;14:419-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Socher I, Andrei-Selmer C, Bein G, et al. Low-avidity HPA-1a alloantibodies in severe neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia are detectable with surface plasmon resonance technology. Transfusion 2009;49:943-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peterson JA, Kanack A, Nayak D, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of low-avidity HPA-1a antibodies in women exposed to HPA-1a during pregnancy. Transfusion 2013;53:1309-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakchoul T, Kubiak S, Krautwurst A, et al. Low-avidity anti-HPA-1a alloantibodies are capable of antigen-positive platelet destruction in the NOD/SCID mouse model of alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Transfusion 2011;51:2455-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peterson JA, Gitter M, Bougie DW, et al. Low-frequency human platelet antigens as triggers for neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Transfusion 2014;54:1286-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

李洪强

医学硕士,副主任医师,自1994年7月起在中国医学科学院血液病医院(血液学研究所)血液内科工作,从事血液系统疾病的临床诊断和治疗工作二十余年,先后在门急诊、红细胞疾病、白细胞疾病、造血干细胞移植、出凝血等多个科室带组,指导住院医师、进修医师和研究生从事诊疗工作。参与的项目曾获得天津市科技进步一等奖,教育部科技进步二等奖,中国现代医院管理医疗信息化与健康医疗大数据典型案例。现为天津市病案质控委员会委员,北京市肿瘤病案信息技术专业委员会委员,中国抗癌协会肿瘤病案委员会委员,《中国医药科学》杂志审稿人。(更新时间:2021/8/31)

丁江华

医学博士,副主任医师,副教授,硕士生导师。现任九江学院附属医院血液肿瘤科副主任。2015年荣获江西省优秀博士学位论文奖。先后承担与参与多项国家、省、市级科研课题。(更新时间:2021/8/12)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Matsuhashi M, Tsuno NH. Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of immune-mediated thrombocytopenia. Ann Blood 2018;3:41.